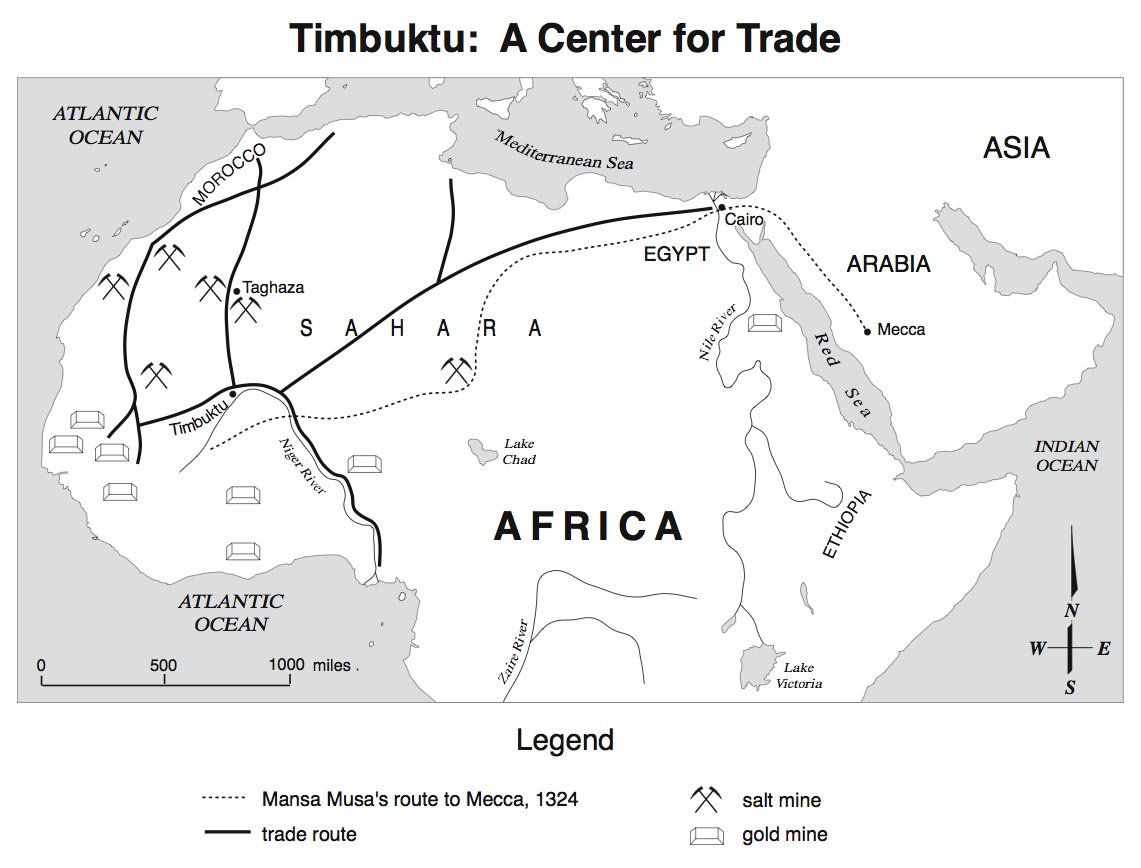

The Richest Man in U.S. History

If you read the prior blog post and guessed that the richest man in U.S. history exploited essential facilities and property rights to get rich, you would be correct. But John D. Rockefeller (I will call him JD) brings a couple more economic principles to light. Before examining JD's get-rich tactics, let's put his wealth in perspective. Mansa Musa reached his maximum wealth of an estimated $400 billion dollars. At his peak, JD controlled about 1.5% of the U.S. output, an equivalent of $350 billion in today's dollars. That is more than double the wealth of either of the two richest men in the world, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

So how did JD do it? He began his career at age 16 working as an assistant bookkeeper. He enthusiastically delved into all aspects of business and, especially, understanding costs. His early mastery of calculating transportation costs would serve him well later in life. At the age of 20, he and a handful of business partners built an oil refinery. At the time, whale oil was used as the primary source of light in homes. Oil held promise as a lower-cost substitute, but the ultimate importance of oil in the world's economies was not anticipated by anyone including JD. Nor was the concept of an essential facility on his mind. Whether by hunch, luck, or his mastery of good business, he had discovered a proverbial gold mine.

Oil refining was (and is) an essential facility. Between extracting oil from the ground and producing final products like kerosene and gasoline, crude oil must go through the refining bottleneck. To fully exploit the essential facility, JD needed the property right to most or all of the oil refining business. By age 26, JD could see glimpses of the future for oil and the industrial revolution and set about securing property rights to domestic refineries. He bought out his partners who sold cheaply not seeing the future JD saw. Just as he was turning 30 he formed Standard of Ohio and quickly became one of the largest shippers of kerosene and oil in the nation. His next step would be to secure property rights to virtually all refineries in the country and, more importantly, to begin the process of vertical and horizontal integration in the market for all oil products.

Horizontal integration is an economic concept that takes advantage of economies of scale. If one makes automobiles one at a time, the time and cost of the car would be absurdly high. On the other hand, by setting up an assembly line that could produce cars on a much larger scale, the cost per car could fall spectacularly. Reducing the marginal cost of producing a car is the result of economies of scale (with each increase in scale, the cost of producing yet another car, the marginal cost, is lowered).

JD recognized that if he were to collect more and more oil refineries under Standard Oil, he could take advantage of economies of scale and undercut the prices of the remaining smaller competitors leaving him alone in control of his prized essential facility.

Vertical integration occurs when one acquires the property rights to other businesses "downstream" (oil wells and crude oil pipelines, for example) and "upstream" (manufacturing and distributing final products to consumers, for example). Complete vertical integration would collect the entire production, refining, and distribution of oil-based products under one company. JD set his sights on both horizontal and vertical integration.

The combination of vertical and horizontal integration creates opportunities for economies of scope. For example, by owning or controlling the transportation of refined oil and final products, JD could reduce the cost of transporting the entire scope of his products by combining many products in one delivery contract and in tankers he owned (Jeff Bezos became the wealthiest man today in part by using a similar tactic). He could make home deliveries of more than one product to a home or business at less cost than making two separate deliveries, and so forth. In other words, he could cut costs by managing his products as a group. JD could control the nation's oil-dependent products from bottom to top. He saw opportunities to control horizontal and vertical businesses without owning everything.

To expand his monopoly power over what he couldn't own in the vertical production chain, he found means of control. For example, he used the enormous volumes of his shipping to negotiate rates as low as half the normal shipping rates. By the time JD approached 40 years of age, in addition to owning oil refineries that produced 90% of the nation's refined oil, he owned pipelines, thousands of oil wells, tank cars, home delivery networks, and had developed over 300 final products using refined oil (including paint, tar and hundreds more). But the United States was beginning to treat monopolizing an industry as an abusive business practice not in the public interest, perhaps even criminal behavior.

At age 40, JD was indicted on charges of monopolizing the oil industry. This threatened JD's property rights that had secured his fortune. But he was far from defeated. JD believed that his business practices were a benefit to the public and to the economy. The price of kerosene had dropped 80% since Standard Oil entered the business, for example. Nevertheless, state legislatures made it difficult or impossible to incorporate in one state and operate in another. To comply with the law, JD's oil interests fragmented into more than 40 companies operating in different states.

But having clever lawyers at his disposal turned the obstacle into an annoyance but not the end of his property rights. He formed the nation's first significant trust. The fragmented companies placed their individual corporate shares of stock in a trust to be managed by the trustees. Nine trustees including JD ran 41 companies consisting of 20,000 domestic wells, 4,000 miles of pipeline, 5,000 tank cars, and over 100,000 employees. The property rights to almost 90% of the world's refining capacity, the oil business's essential facility, remained a property right controlled by JD.

Eventually, antitrust laws strengthened, competition in the oil industry oil throughout the world grew in ways that even JD couldn't control, and JD retired to give much of his fortune to charity.

What JD's story adds to Mansa Musa's story are three things: 1) Property rights in the more modern period operate on a legal and regulatory battlefield rather than on a military battlefield, 2) Horizontal and vertical integration can magnify the value of property rights to essential facilities, and 3) The cost advantages of economies of scale and scope can fortify a business against intrusion from competitors. JD profited from selling at prices competitors could not profitably match.