Note: this is the first in a series of blogs that explore how economic principles have been exploited to make people rich.

Mansa Musa: the African King of Kings

It is impossible to say for certain who in the history of the world accumulated the greatest wealth. You can imagine the difficulties comparing the worth of salt, gold, and land across places and times that had no standard way to count money. Indeed, there is controversy today about how to compare the prices we pay now compared to a year ago. We presently rely on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to compare prices of a "typical" mix of goods most people tend to buy. But if you only bought bananas and someone else only bought wine, you would experience very different changes in the cost of living throughout the year.

Nevertheless, economists have ways of roughly estimating who was the most wealthy person in recorded history. However wealth is measured, there is some (though not unanimous) agreement that an African king, Mansa Musa, was the wealthiest person in history. I will use him to illustrate two economic principles that can be used to make one incomprehensibly wealthy. So how did Mansa Musa get to be so rich and how did his heirs lose it all in two generations?

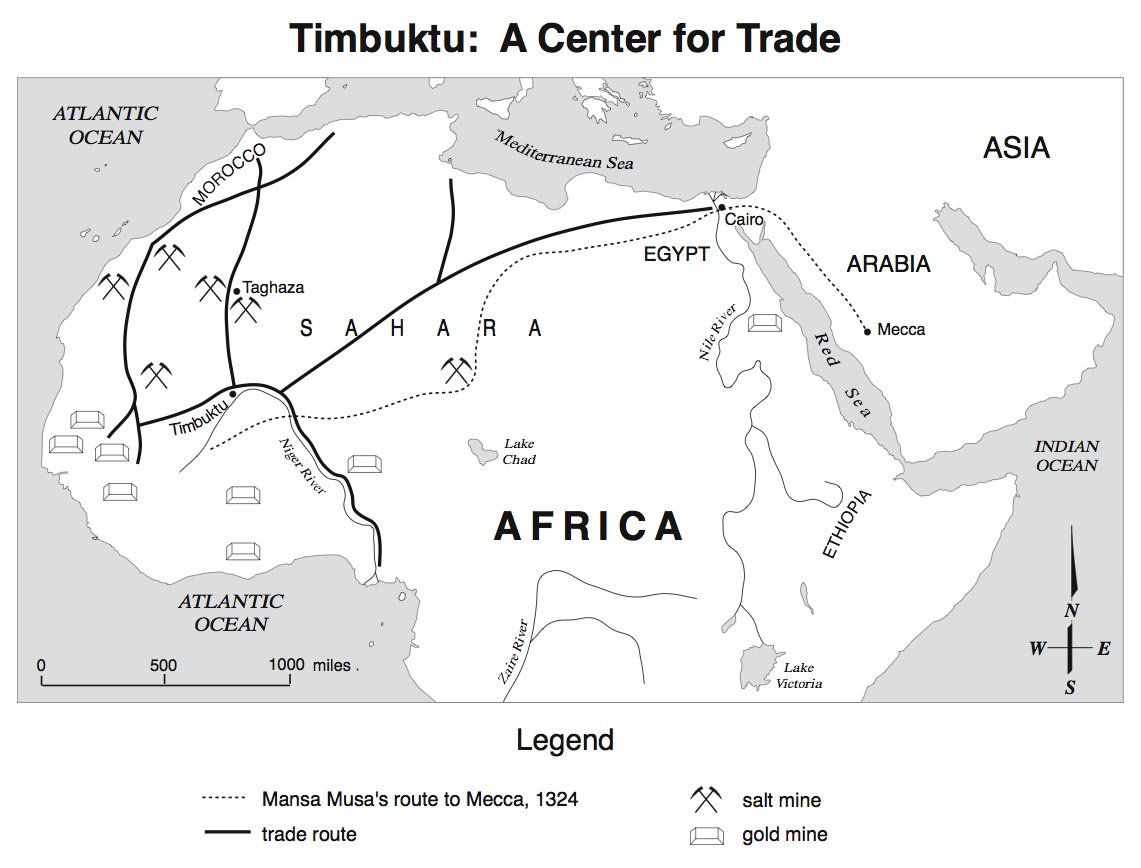

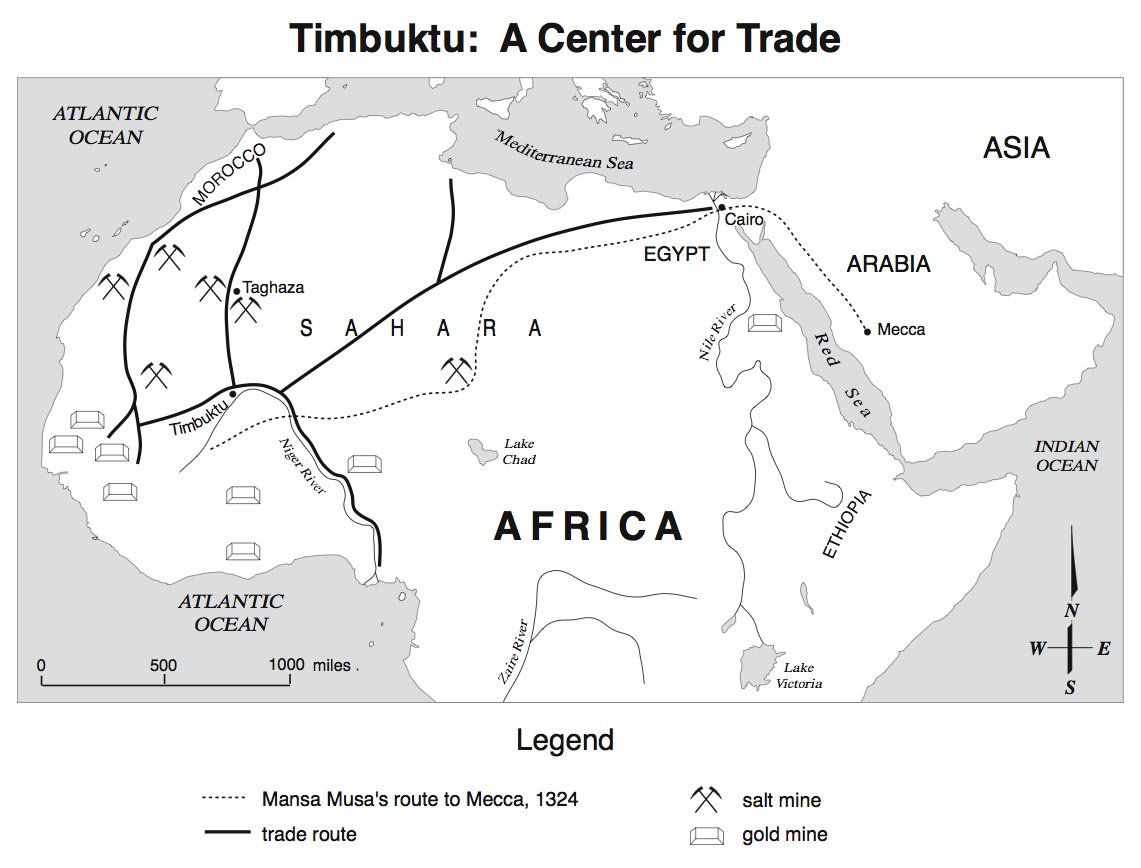

Mansa Musa did not set out to own all the copper mines, salt mines, camels, or riverboats. He acquired and maintained control of what economists call "essential facilities". Most trade moving through Africa was funneled through Mali. Mansa Musa used military force to expand Mali into an empire that spanned all of western Africa. The Mali Empire encompassed virtually all critical junctures in the overland and river trade routes. The Mali Empire contained the most navigable portions of the River Niger used to transport goods by water. The rich soil of the Niger Delta supported an abundance of food and animals to support trade. Mali housed cities that were centers of cultural, religious, educational, and economic activities. In other words, Mali contained all the resources that were necessary to facilitate trade within Africa and between Africa and Eurasia. Without the support of the Mali Empire, Africa's contribution to trade in much of the ancient world would have remained an obscure footnote in history.

Salt and gold were the most important commodities on the trade routes. Salt was mined in the dry Sahara Desert and transported south where it was an essential nutritional supplement replacing the natural body salts lost through sweat. Salt was transported towards the savanna south of Mali. Gold, an essential component of all international trade, was mined in and near the Mali Empire and exported north to international destinations. Only Mansa Musa could legally own gold nuggets inside Mali, only gold dust was used for local trade. Salt and gold were exchanged ounce for ounce on nearly equal terms. In addition, all goods crossing into or out of the Mali Empire (kola nuts, slaves, copper, and other resources) were taxed by Mansa Musa.

One look at the map of trade routes suggests why the Mali Empire, with Timbuktu at its center, became (what economists term) an essential facility in African trade. Without the support and permission of Mali, African trade would come to a halt. That is the nature of essential facilities: critical production and transactions require the essential facility to function. But it takes more than an essential facility to milk it for wealth.

To exploit an essential facility for gain, one needs to establish and sustain a property right to the facility. Thus the concept of a"property right" is the second lesson in economics Mansa Musa teaches us. Musa inherited the property right to Mali and used his military to encompass all major African trade routes.

Musa sustained his property rights in several important ways. He set taxes on trade at levels that didn't invite serious military challenges. He used his extensive military forces to protect merchants using the trade routes for which merchants were appreciative. And he prevented civil revolts by generously giving to the poor. Musa also promoted Islam as a religion of peace and equality among all humans (likely excepting slaves since he facilitated the slave trade on the trade routes). He is best known for his trek to Mecca leading 60,000 people and lavishing gold on the needy along the way (so much so that he depressed gold prices for years after). However, he ruthlessly dealt with any who threatened him or his regime. He had great management skills and built universities, mosques, and safe urban environments. All of these actions served to sustain his property rights to his essential facilities.

When Mansa Musa died, control of the Mali Empire passed to his heirs who lacked this management skills and strategic thinking. They disregarded the need to balance economic power with an understanding of human nature and complex organizational oversight. Within two generations, all the wealth of the empire was lost amid civil unrest, succession disputes, and the inability of Musa's son and older brother to keep Mali'a vassal states from becoming independent.

Mansa Musa did not set out to own all the copper mines, salt mines, camels, or riverboats. He acquired and maintained control of what economists call "essential facilities". Most trade moving through Africa was funneled through Mali. Mansa Musa used military force to expand Mali into an empire that spanned all of western Africa. The Mali Empire encompassed virtually all critical junctures in the overland and river trade routes. The Mali Empire contained the most navigable portions of the River Niger used to transport goods by water. The rich soil of the Niger Delta supported an abundance of food and animals to support trade. Mali housed cities that were centers of cultural, religious, educational, and economic activities. In other words, Mali contained all the resources that were necessary to facilitate trade within Africa and between Africa and Eurasia. Without the support of the Mali Empire, Africa's contribution to trade in much of the ancient world would have remained an obscure footnote in history.

Salt and gold were the most important commodities on the trade routes. Salt was mined in the dry Sahara Desert and transported south where it was an essential nutritional supplement replacing the natural body salts lost through sweat. Salt was transported towards the savanna south of Mali. Gold, an essential component of all international trade, was mined in and near the Mali Empire and exported north to international destinations. Only Mansa Musa could legally own gold nuggets inside Mali, only gold dust was used for local trade. Salt and gold were exchanged ounce for ounce on nearly equal terms. In addition, all goods crossing into or out of the Mali Empire (kola nuts, slaves, copper, and other resources) were taxed by Mansa Musa.

One look at the map of trade routes suggests why the Mali Empire, with Timbuktu at its center, became (what economists term) an essential facility in African trade. Without the support and permission of Mali, African trade would come to a halt. That is the nature of essential facilities: critical production and transactions require the essential facility to function. But it takes more than an essential facility to milk it for wealth.

To exploit an essential facility for gain, one needs to establish and sustain a property right to the facility. Thus the concept of a"property right" is the second lesson in economics Mansa Musa teaches us. Musa inherited the property right to Mali and used his military to encompass all major African trade routes.

Musa sustained his property rights in several important ways. He set taxes on trade at levels that didn't invite serious military challenges. He used his extensive military forces to protect merchants using the trade routes for which merchants were appreciative. And he prevented civil revolts by generously giving to the poor. Musa also promoted Islam as a religion of peace and equality among all humans (likely excepting slaves since he facilitated the slave trade on the trade routes). He is best known for his trek to Mecca leading 60,000 people and lavishing gold on the needy along the way (so much so that he depressed gold prices for years after). However, he ruthlessly dealt with any who threatened him or his regime. He had great management skills and built universities, mosques, and safe urban environments. All of these actions served to sustain his property rights to his essential facilities.

When Mansa Musa died, control of the Mali Empire passed to his heirs who lacked this management skills and strategic thinking. They disregarded the need to balance economic power with an understanding of human nature and complex organizational oversight. Within two generations, all the wealth of the empire was lost amid civil unrest, succession disputes, and the inability of Musa's son and older brother to keep Mali'a vassal states from becoming independent.